On the attrition of our longer-term mission force: Posting 1: Of stories and icebergs

June 16, 2017

Posting 1: Of stories and icebergs

A story

How can I forget that young missionary family in Latin America? He was a missionary kid who had returned to his beloved region with a younger wife and a little girl, and his wife expecting her second. He had dreamed since age 8 that he would be a missionary, and having made that decision, it turned around and shaped his own life. Her radical decisions were made as she finished high school, with the commitment “Anything, anywhere, any price”. When she fell in love with that guy, it meant for her truly leaving home and family, language and culture, the known for the unknown, the orderly for the disorderly. In some senses, she was the “true missionary” just on personal cost. All love.

Finally, for him, after three years of Bible school, a university degree, four years of seminary, and a term of staff ministry with Inter-Varsity, they were off “to the field”, to his “home and language”. Little did he know what he would encounter when his idealized expectations faced reality, or that his dreams would be torpedoed in their first term. Nothing that happened to them could have been found in the “small print of the life-contract” of mission service. He had never heard of the term, “toxic leader”. He had never experienced anything like that before, and from a former friend. Towards the end of the first term he was absolutely worn down, and on the cusp of throwing in the towel and facing a defeated return to his “passport culture” (certainly not his “home country”). He was on the precipice of failure and shattered dreams. Ironically his wife, with no cross-cultural experience, lived her life out of a calm center, focused on God’s character. He was neither calm nor focused anymore.

Late one night during the worst of that personal and vocational darkness, the doorbell rang. The political situation in that nation was delicate (an understatement as we lived under martial law with curfews). People were not out on the street after 10 PM. To his astonishment he found outside the barred gates of their home a greatly respected veteran mission leader who at that time lived in the USA. “What are you doing here in Guatemala? We had no idea you were coming here.” He simply stated, “I have come”, and said no more, refusing to explain his pithy statement. So into the house he came, kissed the wife, looked in on the sleeping little one, then sat down, and simply asked the young worker, “How are you doing?” The TCP husband broke down, and with his wife sitting alongside (she calm), told his painful story in tears. The veteran listened. He discerned the deeper cries. The couple was six months away from a two-year study leave. The veteran asked whether he could hold on that long. Yes, they thought they could.

The veteran spoke healing and promise. Gradually, new perspectives of hope came into focus. Humanly speaking, God used this man to “save” that young family from being an early case of crushing attrition. Saved by the unannounced random appearance of the mission society president, also known as a beloved visionary shepherd.

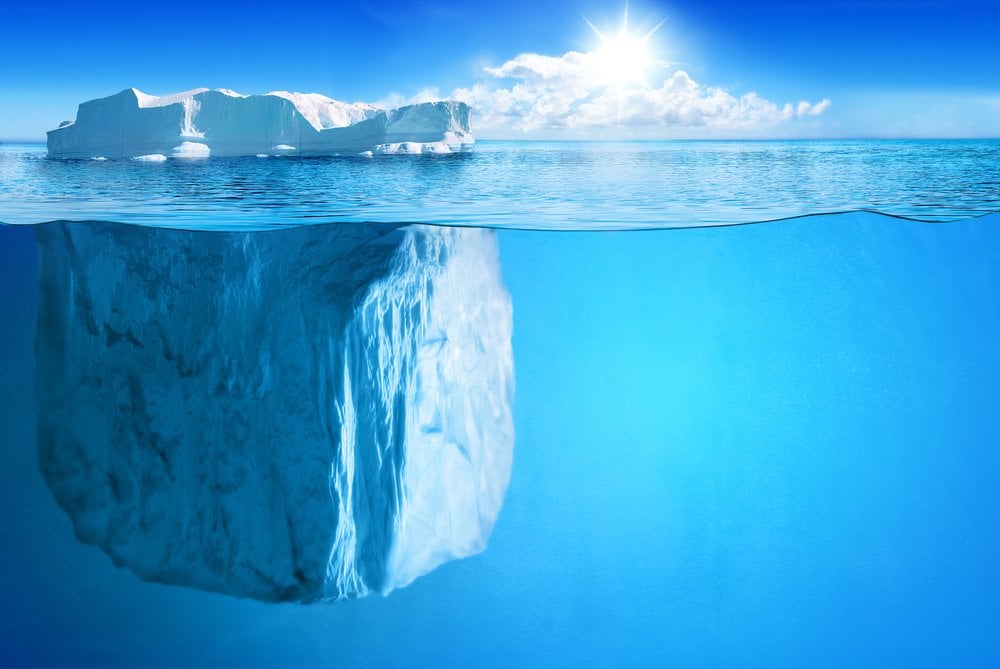

Of icebergs and attrition

We all know something about icebergs, those floating ice masses, broken off from glaciers, their largest portion under water, dangerously hidden from view. Missionary attrition reminds us of icebergs. We tend to see only the top-side visible evidence—i.e., missionaries who, for whatever reason, have permanently left cross-cultural service. During 1993-1997, it was my privilege to play a role in a 14-nation study of attrition through the leadership of the Mission Commission, World Evangelical Alliance. Following the research, in mid 1996, a select group was convened at All Nations Christian College in the UK, and in 1997 the book, Too Valuable to Lose: Exploring the Causes and Cures of Missionary Attrition was released.

Our MC leadership team had been reminded again and again of the hidden dimensions of attrition—for example, the “real” reasons why missionaries leave, or the invisible culture of the mission society/agency that clearly affects attrition positively or negatively. We also suspected there were significant differences between what we called then the “Older Sending Countries” and the “Newer Sending Countries”. We would discover significant insights in the Korean study of first term workers. We developed new categories, such as “preventable attrition” and its counter, “unpreventable” or “painful” attrition.

In this series of posting

I want to engage some of my own reflections on missionary attritions. It will start with the introductory thoughts. We will define some key terms. We will summarize those 1996 findings again. We will visit the broader study on retention and best practices that we did a decade later under the team led by Rob Hay (most recently) of Redcliffe College and the 2013 key book, Worth Keeping: Global Perspectives on Best Practice in Missionary Retention.

The first strands of this series comes from my introduction and involvement in the watershed book, Too Valuable to Lose: Exploring the Causes and Cures for Missionary Attrition, which I edited and WCL published in 1996. But as I read and re-read that introduction, I realized that I had changed, the world had changed, and thus our writing to address these issues must change.

Another blog will reference the key people who have shaped my thinking on this topic. And I want to address how the entire set of categories and language of attrition has changed for today. We visit the issues for older-generation, mid-generation, younger-generation workers. We will examine how the global refugee migrations are affecting mission service, and the unique opportunity they offer to present compassion and justice, Gospel and Christian community, a true living out of the Nazareth Manifesto of Luke 4.

Why have I been mulling these issues over all my life? Well, my parents were cross-cultural workers, launched into Latin America in 1938. As I grew up I met other workers, saw them serve, and too many of them seemed (to a child) just to disappear. I never asked questions in those years. But I witnessed a lot. However, during the last 50 years I have pro-actively observed long-term cross-cultural workers come and go, but for many years I never asked the hard questions. I certainly was not aware of the underlying causes (unless they were really obvious to all). So my blog grapples with many case studies, personal observations, readings and the result of the two major WEA MC studies on attrition and retention.

A final personal note.

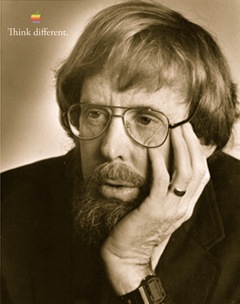

That young missionary of the first paragraphs? Yes, his name was Bill Taylor, married to Yvonne Christine DeAcutis Taylor. And the mission leader? His father, Dr. William H. Taylor, a visionary shepherd, a man of God. “I have come” has entered the legendary phrases of my life, and that was one of Dad’s preferred modes of speaking to me: short, pithy, unexplained aphorisms. He had NO idea of my brokenness in 1972, and to this day I have no idea why he made the trip to Guatemala. Had the Spirit spoken to him in a dream? Perhaps so.

Next post: probing deeper into attrition heart and reality